Interpreters and compilers are interesting programs, themselves used to run or translate other programs, respectively. Those other programs that might be interpreted might be languages like JavaScript, Ruby, Python, PHP, and Perl. The other programs that might be compiled are C, C++, and to some extent Java and C#.

Taking the time to do translation to native machine code ahead of time can result in better performance at runtime, but an interpreter can get to work right away without spending any time translating. There happens to be a sweet spot somewhere in between interpretation and compilation that combines the best of both worlds. Such a technique is called Just In Time (JIT) compiling. While interpreting, compiling, and JIT’ing code might sound radically different, they’re actually strikingly similar. In this post, I hope to show how similar by comparing the code for an interpreter, a compiler, and a JIT compiler for the language Brainfuck in around 100 lines of C code each.

All of the code in the post is up on GitHub.

Brainfuck is an interesting, if hard to read, language. It only has eight

operations it can perform > < + - . , [ ], yet is Turing complete. There’s nothing really to

lex; each character is a token, and if the token is not one of the eight

operators, it’s ignored. There’s also not much of a grammar to parse; the

forward jumping and backwards jumping operators should be matched for well

formed input, but that’s about it. In this post, we’ll skip over validating

input assuming well formed input so we can focus on the interpretation/code

generation. You can read more about it on the

Wikipedia page,

which we’ll be using as a reference throughout.

A Brainfuck program operates on a 30,000 element byte array initialized to all zeros. It starts off with an instruction pointer, that initially points to the first element in the data array or “tape.” In C code for an interpreter that might look like:

// Initialize the tape with 30,000 zeroes.

unsigned char tape [30000] = { 0 };

// Set the pointer to point at the left most cell of the tape.

unsigned char* ptr = tape;

Then, since we’re performing an operation for each character in the Brainfuck source, we can have a for loop over every character with a nested switch statement containing case statements for each operator.

The first two operators, > and < increment and decrement the data pointer.

case '>': ++ptr; break;

case '<': --ptr; break;

One thing that could be bad is that because the interpreter is written in C and we’re representing the tape as an array but we’re not validating our inputs, there’s potential for stack buffer overrun since we’re not performing bounds checks. Again, punting and assuming well formed input to keep the code and the point more precise.

Next up are the + and - operators, used for incrementing and decrementing

the cell pointed to by the data pointer by one.

case '+': ++(*ptr); break;

case '-': --(*ptr); break;

The operators . and , provide Brainfuck’s only means of input or output, by

writing the value pointed to by the instruction pointer to stdout as an ASCII

value, or reading one byte from stdin as an ASCII value and writing it to the

cell pointed to by the instruction pointer.

case '.': putchar(*ptr); break;

case ',': *ptr = getchar(); break;

Finally, our looping constructs, [ and ]. From the definition on Wikipedia

for [: if the byte at the data pointer is zero, then instead of moving the instruction pointer forward to the next command, jump it forward to the command after the matching ] command and for ]: if the byte at the data pointer is nonzero, then instead of moving the instruction pointer forward to the next command, jump it back to the command after the matching [ command.

I interpret that as:

case '[':

if (!(*ptr)) {

int loop = 1;

while (loop > 0) {

unsigned char current_char = input[++i];

if (current_char == ']') {

--loop;

} else if (current_char == '[') {

++loop;

}

}

}

break;

case ']':

if (*ptr) {

int loop = 1;

while (loop > 0) {

unsigned char current_char = input[--i];

if (current_char == '[') {

--loop;

} else if (current_char == ']') {

++loop;

}

}

}

break;

Where the variable loop keeps track of open brackets for which we’ve not seen

a matching close bracket, aka our nested depth.

So we can see the interpreter is quite basic, in around 50 SLOC were able to read a byte, and immediately perform an action based on the operator. How we perform that operation might not be the fastest though.

How about if we want to compile the Brainfuck source code to native machine code? Well, we need to know a little bit about our host machine’s Instruction Set Architecture (ISA) and Application Binary Interface (ABI). The rest of the code in this post will not be as portable as the above C code, since it assumes an x86-64 ISA and UNIX ABI. Now would be a good time to take a detour and learn more about writing assembly for x86-64. The interpreter is even portable enough to build with Emscripten and run in a browser!

For our compiler, we’ll iterate over every character in the source file again, switching on the recognized operator. This time, instead of performing an action right away, we’ll print assembly instructions to stdout. Doing so requires running the compiler on an input file, redirecting stdout to a file, then running the system assembler and linker on that file. We’ll stick with just compiling and not assembling (though it’s not too difficult), and linking (for now).

First, we need to print a prologue for our compiled code:

const char* const prologue =

".text\n"

".globl _main\n"

"_main:\n"

" pushq %rbp\n"

" movq %rsp, %rbp\n"

" pushq %r12\n" // store callee saved register

" subq $30008, %rsp\n" // allocate 30,008 B on stack, and realign

" leaq (%rsp), %rdi\n" // address of beginning of tape

" movl $0, %esi\n" // fill with 0's

" movq $30000, %rdx\n" // length 30,000 B

" call _memset\n" // memset

" movq %rsp, %r12";

puts(prologue);

During the linking phase, we’ll make sure to link in libc so we can call

memset. What we’re doing is backing up callee saved registers we’ll be using,

stack allocating the tape, realigning the stack (

x86-64 ABI point #1), copying

the address of the only item on the stack into a register for our first

argument, setting the second argument to the constant 0, the third arg to

30000, then calling memset. Finally, we use the callee saved register %r12

as our instruction pointer, which is the address into a value on the stack.

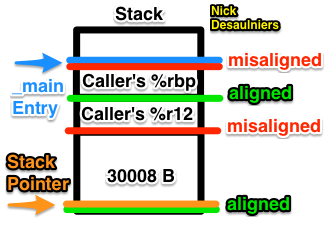

We can expect the call to memset to result in a segfault if simply subtract just 30000B, and not realign for the 2 registers (64 b each, 8 B each) we pushed on the stack. The first pushed register aligns the stack on a 16 B boundary, the second misaligns it; that’s why we allocate an additional 8 B on the stack ( x86-64 ABI point #1). The stack is mis-aligned upon function entry in x86-64. 30000 is a multiple of 16.

Moving the instruction pointer (>, <) and modifying the pointed to value

(+, -) are straight-forward:

case '>':

puts(" inc %r12");

break;

case '<':

puts(" dec %r12");

break;

case '+':

puts(" incb (%r12)");

break;

case '-':

puts(" decb (%r12)");

break;

For output, ., we need to copy the pointed to byte into the register for the

first argument to putchar. We

explicitly zero out the register before calling putchar, since it takes an int

(32 b), but we’re only copying a char (8 b) (Look up C’s type promotion rules for more info). x86-64 has an instruction that does both, movzXX, Where the first X is the source size (b, w) and the second is the destination size (w, l, q). Thus movzbl moves a byte (8 b) into a double word (32 b). %rdi and %edi are the same register, but %rdi is the full

64 b register, while %edi is the lowest (or least significant) 32 b.

case '.':

// move byte to double word and zero upper bits since putchar takes an

// int.

puts(" movzbl (%r12), %edi");

puts(" call _putchar");

break;

Input (,) is easy; call getchar, move the resulting lowest byte into the cell

pointed to by the instruction pointer. %al is the lowest 8 b of the 64 b %rax register.

case ',':

puts(" call _getchar");

puts(" movb %al, (%r12)");

break;

As usual, the looping constructs ([ & ]) are much more work. We have to

match up jumps to matching labels, but for an assembly program, labels must be

unique. One way we can solve for this is whenever we encounter an opening

brace, push a monotonically increasing number that represents the numbers of

opening brackets we’ve seen so far onto a stack like data structure. Then, we

do our comparison and jump to what will be the label that should be produced by

the matching close label. Next, we insert our starting label, and finally

increment the number of brackets seen.

case '[':

stack_push(&stack, num_brackets);

puts(" cmpb $0, (%r12)");

printf(" je bracket_%d_end\n", num_brackets);

printf("bracket_%d_start:\n", num_brackets++);

break;

For close brackets, we pop the number of brackets seen (or rather, number of pending open brackets which we have yet to see a matching close bracket) off of the stack, do our comparison, jump to the matching start label, and finally place our end label.

case ']':

stack_pop(&stack, &matching_bracket);

puts(" cmpb $0, (%r12)");

printf(" jne bracket_%d_start\n", matching_bracket);

printf("bracket_%d_end:\n", matching_bracket);

break;

So for sequential loops ([][]) we can expect the relevant assembly to look

like:

cmpb $0, (%r12)

je bracket_0_end

bracket_0_start:

cmpb $0, (%r12)

jne bracket_0_start

bracket_0_end:

cmpb $0, (%r12)

je bracket_1_end

bracket_1_start:

cmpb $0, (%r12)

jne bracket_1_start

bracket_1_end:

and for nested loops ([[]]), we can expect assembly like the following (note

the difference in the order of numbered start and end labels):

cmpb $0, (%r12)

je bracket_0_end

bracket_0_start:

cmpb $0, (%r12)

je bracket_1_end

bracket_1_start:

cmpb $0, (%r12)

jne bracket_1_start

bracket_1_end:

cmpb $0, (%r12)

jne bracket_0_start

bracket_0_end:

Finally, we need an epilogue to clean up the stack and callee saved registers after ourselves.

const char* const epilogue =

" addq $30008, %rsp\n" // clean up tape from stack.

" popq %r12\n" // restore callee saved register

" popq %rbp\n"

" ret\n";

puts(epilogue);

The compiler is a pain when modifying and running a Brainfuck program; it takes a couple extra commands to compile the Brainfuck program to assembly, assemble the assembly into an object file, link it into an executable, and run it whereas with the interpreter we can just run it. The trade off is that the compiled version is quite a bit faster. How much faster? Let’s save that for later.

Wouldn’t it be nice if there was a translation & execution technique that didn’t force us to compile our code every time we changed it and wanted to run it, but also performed closer to that of compiled code? That’s where a JIT compiler comes in!

For the basics of JITing code, make sure you read my previous article on the basics of JITing code in C. We’re going to follow the same technique of creating executable memory, copying bytes into that memory, casting it to a function pointer, then calling it. Just like the interpreter and the compiler, we’re going to do a unique action for each recognized token. What’s different is that for each operator, we’re going to push opcodes into a dynamic array, that way it can grow based on our sequential reading of input and will simplify our calculation of relative offsets for branching operations.

The other special thing we’re going to do it that we’re going to pass the address of our libc functions (memset, putchar, and getchar) into our JIT’ed function at runtime. This avoids those kooky stub functions you might see in a disassembled executable. That means we’ll be invoking our JIT’ed function like:

typedef void* fn_memset (void*, int, size_t);

typedef int fn_putchar (int);

typedef int fn_getchar ();

void (*jitted_func) (fn_memset, fn_putchar, fn_getchar) = mem;

jitted_func(memset, putchar, getchar);

Where mem is our mmap’ed executable memory with our opcodes copied into it, and the typedef’s are for the respective function signatures for our function pointers we’ll be passing to our JIT’ed code. We’re kind of getting ahead of ourselves, but knowing how we will invoke the dynamically created executable code will give us an idea of how the code itself will work.

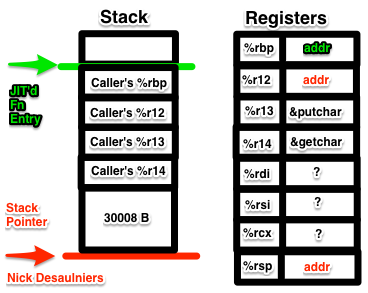

The prologue is quite a bit involved, so we’ll take it step at a time. First, we have the usual prologue:

char prologue [] = {

0x55, // push rbp

0x48, 0x89, 0xE5, // mov rsp, rbp

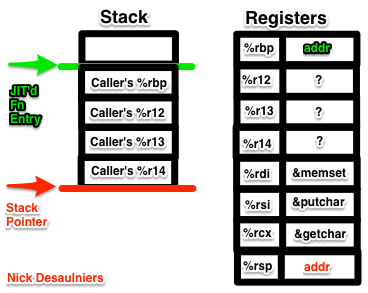

Then we want to back up our callee saved registers that we’ll be using. Expect horrific and difficult to debug bugs if you forget to do this.

0x41, 0x54, // pushq %r12

0x41, 0x55, // pushq %r13

0x41, 0x56, // pushq %r14

At this point, %rdi will contain the address of memset, %rsi will contain the address of putchar, and %rdx will contain the address of getchar, see x86-64 ABI point #2. We want to store these in callee saved registers before calling any of them, else they may clobber %rdi, %rsi, or %rdx since they’re not “callee saved,” rather “call clobbered.” See x86-64 ABI point #4.

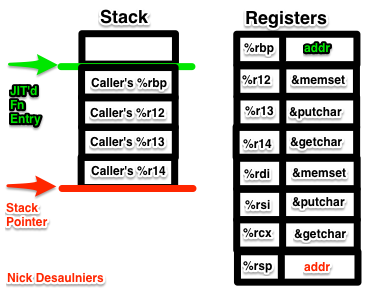

0x49, 0x89, 0xFC, // movq %rdi, %r12

0x49, 0x89, 0xF5, // movq %rsi, %r13

0x49, 0x89, 0xD6, // movq %rdx, %r14

At this point, %r12 will contain the address of memset, %r13 will contain the address of putchar, and %r14 will contain the address of getchar.

Next up is allocating 30008 B on the stack:

0x48, 0x81, 0xEC, 0x38, 0x75, 0x00, 0x00, // subq $30008, %rsp

This is our first hint at how numbers, whose value is larger than the maximum

representable value in a byte, are represented on x86-64. Where in this

instruction is the value 30008? The answer is the 4 byte sequence

0x38, 0x75, 0x00, 0x00. The x86-64 architecture is “Little Endian,” which

means that the least significant bit (LSB) is first and the most significant

bit (MSB) is last. When humans do math, they typically represent numbers the

other way, or “Big Endian.” Thus we write decimal ten as “10” and not “01.”

So that means that 0x38, 0x75, 0x00, 0x00 in Little Endian is

0x00, 0x00, 0x75, 0x38 in Big Endian, which then is

7*16^3+5*16^2+3*16^1+8*16^0

which is 30008 in decimal, the amount of bytes we want to subtract from the

stack. We’re allocating an additional 8 B on the stack for alignment

requirements, similar to the compiler. By pushing even numbers of 64 b

registers, we need to realign our stack pointer.

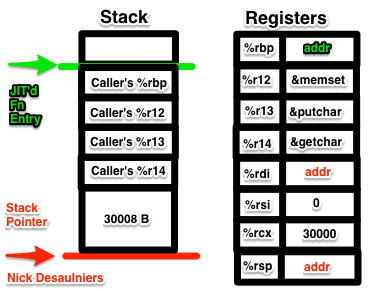

Next in the prologue, we set up and call memset:

// address of beginning of tape

0x48, 0x8D, 0x3C, 0x24, // leaq (%rsp), %rdi

// fill with 0's

0xBE, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, // movl $0, %esi

// length 30,000 B

0x48, 0xC7, 0xC2, 0x30, 0x75, 0x00, 0x00, // movq $30000, %rdx

// memset

0x41, 0xFF, 0xD4, // callq *%r12

After invoking memset, %rdi, %rsi, & %rcx will contain garbage values since they are “call clobbered” registers. At this point we no longer need memset, so we now use %r12 as our instruction pointer. %rsp will point to the top (technically the bottom) of the stack, which is the beginning of our memset’ed tape. That’s the end of our prologue.

0x49, 0x89, 0xE4 // movq %rsp, %r12

};

We can then push our prologue into our dynamic array implementation:

vector_push(&instruction_stream, prologue, sizeof(prologue))

Now we iterate over our Brainfuck program and switch on the operations again. For pointer increment and decrement, we just nudge %r12.

case '>':

{

char opcodes [] = {

0x49, 0xFF, 0xC4 // inc %r12

};

vector_push(&instruction_stream, opcodes, sizeof(opcodes));

}

break;

case '<':

{

char opcodes [] = {

0x49, 0xFF, 0xCC // dec %r12

};

vector_push(&instruction_stream, opcodes, sizeof(opcodes));

}

break;

That extra fun block in the switch statement is because in C/C++, we can’t define variables in the branches of switch statements.

Pointer deref then increment/decrement are equally uninspiring:

case '+':

{

char opcodes [] = {

0x41, 0xFE, 0x04, 0x24 // incb (%r12)

};

vector_push(&instruction_stream, opcodes, sizeof(opcodes));

}

break;

case '-':

{

char opcodes [] = {

0x41, 0xFE, 0x0C, 0x24 // decv (%r12)

};

vector_push(&instruction_stream, opcodes, sizeof(opcodes));

}

break;

I/O might be interesting, but in x86-64 we have an opcode for calling the function at the end of a pointer. %r13 contains the address of putchar while %r14 contains the address of getchar.

case '.':

{

char opcodes [] = {

0x41, 0x0F, 0xB6, 0x3C, 0x24, // movzbl (%r12), %edi

0x41, 0xFF, 0xD5 // callq *%r13

};

vector_push(&instruction_stream, opcodes, sizeof(opcodes));

}

break;

case ',':

{

char opcodes [] = {

0x41, 0xFF, 0xD6, // callq *%r14

0x41, 0x88, 0x04, 0x24 // movb %al, (%r12)

};

vector_push(&instruction_stream, opcodes, sizeof(opcodes));

}

break;

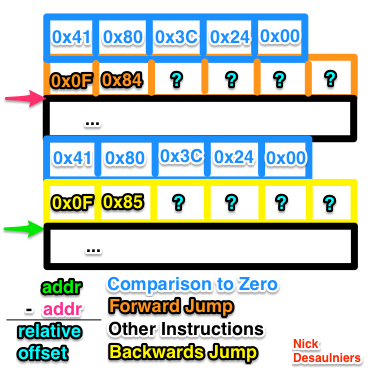

Now with our looping constructs, we get to the fun part. With the compiler, we deferred the concept of “relocation” to the assembler. We simply emitted labels, that the assembler turned into relative offsets (jumps by values relative to the last byte in the jump instruction). We’ve found ourselves in a Catch-22 though: how many bytes forward do we jump to the matching close bracket that we haven’t seen yet?

Normally, an assembler might have a data structure known as a “relocation table.” It keeps track of the first byte after a label and jumps, rewriting jumps-to-labels (which aren’t kept around in the resulting binary executable) to relative jumps. Spidermonkey, Firefox’s JavaScript Virtual Machine has two classes for this, MacroAssembler and Label. Spidermonkey embeds a linked list in the opcodes it generates for jumps with which it’s yet to see a label for. Once it finds the label, it walks the linked list (which itself is embedded in the emitted instruction stream) patching up these locations as it goes.

For Brainfuck, we don’t have to anything quite as fancy since each label only ends up having one jump site. Instead, we can use a stack of integers that are offsets into our dynamic array, and do the relocation once we know where exactly we’re jumping to.

case '[':

{

char opcodes [] = {

0x41, 0x80, 0x3C, 0x24, 0x00, // cmpb $0, (%r12)

// Needs to be patched up

0x0F, 0x84, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00 // je <32b relative offset, 2's compliment, LE>

};

vector_push(&instruction_stream, opcodes, sizeof(opcodes));

}

stack_push(&relocation_table, instruction_stream.size); // create a label after

break;

First we push the compare and jump opcodes, but for now we leave the relative offset blank (four zero bytes). We will come back and patch it up later. Then, we push the current length of dynamic array, which just so happens to be the offset into the instruction stream of the next instruction.

All of the relocation magic happens in the case for the closing bracket.

case ']':

{

char opcodes [] = {

0x41, 0x80, 0x3C, 0x24, 0x00, // cmpb $0, (%r12)

// Needs to be patched up

0x0F, 0x85, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00 // jne <33b relative offset, 2's compliment, LE>

};

vector_push(&instruction_stream, opcodes, sizeof(opcodes));

}

// ...

First, we push our comparison and jump instructions into the dynamic array. We should know the relative offset we need to jump back to at this point, and thus don’t need to push four empty bytes, but it makes the following math a little simpler, as were not done yet with this case.

// ...

stack_pop(&relocation_table, &relocation_site);

relative_offset = instruction_stream.size - relocation_site;

// ...

We pop the matching offset into the dynamic array (from the matching open bracket), and calculate the difference from the current size of the instruction stream to the matching offset to get our relative offset. What’s interesting is that this offset is equal in magnitude for the forward and backwards jumps that we now need to patch up. We simply go back in our instruction stream 4 B, and write that relative offset negated as a 32 b LE number (patching our backwards jump), then go back to the site of our forward jump minus 4 B and write that relative offset as a 32 b LE number (patching our forwards jump).

// ...

vector_write32LE(&instruction_stream, instruction_stream.size - 4, -relative_offset);

vector_write32LE(&instruction_stream, relocation_site - 4, relative_offset);

break;

Thus, when writing a JIT, one must worry about manual relocation. From the Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer’s Manual Volume 2 (2A, 2B & 2C): Instruction Set Reference, A-Z “A relative offset (rel8, rel16, or rel32) is generally specified as a label in assembly code, but at the machine code level, it is encoded as a signed, 8-bit or 32-bit immediate value, which is added to the instruction pointer.”

The last thing we push onto our instruction stream is clean up code in the epilogue.

char epilogue [] = {

0x48, 0x81, 0xC4, 0x38, 0x75, 0x00, 0x00, // addq $30008, %rsp

// restore callee saved registers

0x41, 0x5E, // popq %r14

0x41, 0x5D, // popq %r13

0x41, 0x5C, // popq %r12

0x5d, // pop rbp

0xC3 // ret

};

vector_push(&instruction_stream, epilogue, sizeof(epilogue));

A dynamic array of bytes isn’t really useful, so we need to create executable memory the size of the current instruction stream and copy all of the machine opcodes into it, cast it to a function pointer, call it, and finally clean up:

void* mem = mmap(NULL, instruction_stream.size, PROT_WRITE | PROT_EXEC,

MAP_ANON | MAP_PRIVATE, -1, 0);

memcpy(mem, instruction_stream.data, instruction_stream.size);

void (*jitted_func) (fn_memset, fn_putchar, fn_getchar) = mem;

jitted_func(memcpy, putchar, getchar);

munmap(mem, instruction_stream.size);

vector_destroy(&instruction_stream);

Note: we could have used the instruction stream rewinding technique to move the address of memset, putchar, and getchar as 64 b immediate values into %r12-%r14, which would have simplified our JIT’d function’s type signature.

Compile that, and we now have a function that will JIT compile and execute Brainfuck in roughly 141 SLOC. And, we can make changes to our Brainfuck program and not have to recompile it like we did with the Brainfuck compiler.

Hopefully it’s becoming apparent how similar an interpreter, compiler, and JIT

behave. In the interpreter, we immediately execute some operation. In the

compiler, we emit the equivalent text based assembly instructions corresponding

to what the higher level language might get translated to in the interpreter.

In the JIT, we emit the binary opcodes into executable memory and manually

perform relocation, where the binary opcodes are equivalent to the text based

assembly we might emit in the compiler. A production ready JIT would probably have macros for each operation in the JIT would perform, so the code would look more like the compiler rather than raw arrays of bytes (though the preprocessor would translate those macros into such). The entire process is basically disassembling C code with gobjdump -S -M suffix a.out, and punching in hex like one would a Gameshark.

Compare pointer incrementing from the three:

Interpreter:

case '>': ++ptr; break;

Compiler:

case '>':

puts(" inc %r12");

break;

JIT:

case '>':

{

char opcodes [] = {

0x49, 0xFF, 0xC4 // inc %r12

};

vector_push(&instruction_stream, opcodes, sizeof(opcodes));

}

break;

Or compare the full sources of the the interpreter, the compiler, and the JIT. Each at ~100 lines of code should be fairly easy to digest.

Let’s now examine the performance of these three. One of the longer running Brainfuck programs I can find is one that prints the Mandelbrot set as ASCII art to stdout.

Running the UNIX command time on the interpreter, compiled

result, and the JIT, we should expect numbers similar to:

$ time ./interpreter ../samples/mandelbrot.b

43.54s user 0.03s system 99% cpu 43.581 total

$ ./compiler ../samples/mandelbrot.b > temp.s; ../assemble.sh temp.s; time ./a.out

3.24s user 0.01s system 99% cpu 3.254 total

$ time ./jit ../samples/mandelbrot.b

3.27s user 0.01s system 99% cpu 3.282 total

The interpreter is an order of magnitude slower than the compiled result or run of the JIT. Then again, the interpreter isn’t able to jump back and forth as efficiently as the compiler or JIT, since it scans back and forth for matching brackets O(N), while the other two can jump to where they need to go in a few instructions O(1). A production interpreter would probably translate the higher level language to a byte code, and thus be able to calculate the offsets used for jumps directly, rather than scanning back and forth.

The interpreter bounces back and forth between looking up an operation, then doing something based on the operation, then lookup, etc.. The compiler and JIT preform the translation first, then the execution, not interleaving the two.

The compiled result is the fastest, as expected, since it doesn’t have the overhead the JIT does of having to read the input file or build up the instructions to execute at runtime. The compiler has read and translated the input file ahead of time.

What if we take into account the time it takes to compile the source code, and run it?

$ time (./compiler ../samples/mandelbrot.b > temp.s; ../assemble.sh temp.s; ./a.out)

3.27s user 0.08s system 99% cpu 3.353 total

Including the time it takes to compile the code then run it, the compiled results are now slightly slower than the JIT (though I bet the multiple processes we start up are suspect), but with the JIT we pay the price to compile each and every time we run our code. With the compiler, we pay that tax once. When compilation time is cheap, as is the case with our Brainfuck compiler & JIT, it makes sense to prefer the JIT; it allows us to quickly make changes to our code and re-run it. When compilation is expensive, we might only want to pay the compilation tax once, especially if we plan on running the program repeatedly.

JIT’s are neat but compared to compilers can be more complex to implement. They also repeatedly re-parse input files and re-build instruction streams at runtime. Where they can shine is bridging the gap for dynamically typed languages where the runtime itself is much more dynamic, and thus harder (if not, impossible) to optimize ahead of time. Being able to jump into JIT’d native code from an interpreter and back gives you the best of both (interpreted and compiled) worlds.