…"‘Our speech interposes itself between apprehension and truth like a dusty pane or warped mirror. The tongue of Eden was like a flawless glass; a light of total understanding streamed through it. Thus Babel was a second Fall.’ And Isaac the Blind, an early Kabbalist, said that, to quote Gershom Scholem’s translation, ‘The speech of men is connected with divine speech and all language whether heavenly or human derives from one source: the Divine Name.’ The practical kabbalists, the sorcerers, bore the title Ba’al Shem, meaning ‘master of the divine name.’"

“The machine language of the world,” Hiro says.

“Is this another analogy?”

“Computers speak machine language,” Hiro says. “It’s written in ones and zeroes - binary code. At the lowest level, all computers are programmed with strings of ones and zeroes. When you program in machine language, you are controlling the computer at its brainstem, the root of its existence. It’s the tongue of Eden. But it’s very difficult to work in machine language because you go crazy after a while, working at such a minute level. So a whole Babel of computer languages has been created for programmers: FORTRAN, BASIC, COBOL, LISP, Pascal, C, PROLOG, FORTH. You talk to the computer in one of these languages, and a piece of software called a compiler converts it into machine language. But you never can tell exactly what the compiler is doing. It doesn’t always come out the way you want. Like a dusty pane or warped mirror. A really advanced hacker comes to understand the true inner workings of the machine – he sees through the language he’s working in and glimpses the secret functioning of the binary code – becomes a Ba’al Shem of sorts.”

This a beautiful quote, one that I think truly captures the relationship between higher level languages and the Instruction Set Architecture (ISA)’s machine code, though this is from the angle of controlling the machine with its implementation specific quirks which can detract from what you’re actually trying to do.

This blog is meant for those who don’t know x86-64 assembly, but maybe know a little C, and are curious about code generation. Or maybe if you’ve ever tried to hand write x86-64 assembly, and got stuck trying to understand the tooling or seemingly random segfaults from what appears to be valid instructions.

I really enjoy writing code in CoffeeScript and C, so I have a quick anecdote about CoffeeScript though you don’t need to know the language. When writing CoffeeScript, I find myself frequently using a vim plugin to view the emitted JavaScript. I know when CoffeeScript emits less than optimal JavaScript. For example in the code:

nick = -> console.log x for x in [0..100]

I know that CoffeeScript is going to push the results of the call to

console.log into an array

and return that, because of the implicit return of the final expression in a

function body, which in this case happens to be a for loop (array comprehension

being treated itself as an expression). The emitted JavaScript looks like:

var nick;

nick = function() {

var x, _i, _results;

_results = [];

for (x = _i = 0; _i <= 100; x = ++_i) {

_results.push(console.log(x));

}

return _results;

};

By putting a seemingly meaningless undefined statement as the final statement in the function body, we can significantly reduce what the function is doing and decrease the number of allocations:

nick = ->

console.log x for x in [0..100]

undefined

emits:

nick = function() {

var x, _i;

for (x = _i = 0; _i <= 100; x = ++_i) {

console.log(x);

}

return void 0;

};

That return void 0 may seem odd, but functions in JavaScript without an

explicit return value return undefined, but since the undefined identifier

can be reassigned to, the expression void 0

evaluates to the value

undefined.

You can see that making the CoffeeScript function body slightly longer and

adding a seemingly meaningless lone undefined statement at the end of the

function body, the emitted JavaScript does not allocate an array or waste time

pushing the results of console.log, which would be undefined, into that

array a hundred times. This reminds me of how seemingly meaningless noop

instructions can keep a processor’s pipeline full by preventing stalls, though

a pipeline stall doesn’t change the correctness of a program, so it’s an

imperfect analogy.

Now I’m not saying that you should be thinking about these kinds of optimizations when programming at such a high level, as they might be premature. I shared with you this example because while writing C code, and reading Michael Abrash’s Graphics Programming Black Book, I wondered to myself if hardcore C programmers also would know the equivalent assembly instructions that would be emitted from their higher level C code (before optimizing compilers even existed).

In college, I was taught 68k and MIPS ISAs. To understand x86-64 we need to be able to write and run it. Unfortunately, I did not have the training to know how to do so. My 68k code was run on a MCU from a FreeScale IDE in Windows, so the process might as well have been indistinguishable from magic to me. I understood that you’d start with low level source, in (somewhat) human readable instructions that would be converted to binary representing op codes. The assembler would then translate the assembly into non-executable object files that contained binary code that had placeholders for sections of code defined in other object files. The linker would then be used to replace the placeholders with the now combined binary code’s relative positions and then converted into an executable. But how do I do this from my x86-64 machine itself? The goto book I’ve been recommended many times is Professional Assembly Language by Richard Blum, but this book only covers x86, not x86-64. There’s been some very big changes to the ABI between x86 and x86-64. You may be familiar with Application Programmer Interfaces ( APIs), but what is an Application Binary Interface? I think of an ABI as how two pieces of native code interact with one another, such as calling convention (how arguments are passed to functions at the ISA level).

I’m very lucky to have the privilege to work with a compiler engineer, Dan Gohman, who has worked on a variety of compilers. I was citing a particular email of Dan’s for some time before he came to work with us, when I would talk about how the naming of LLVM gives the imagery of a virtual machine, though it’s more so a compiler intermediate representation. Dan is an amazing and patient resource who has helped me learn more about the subtleties of the x86-64 ABI. Throughout this blog, I’ll copy some responses to questions I’ve had answered by Dan.

Our first goal is to write an x86-64 program that does nothing, but that we can

build. Assembly files typically have the .s file extension, so let’s fire up

our text editor and get started. I’ll be doing my coding from OSX 10.8.5, but

most examples will work from Linux. All of my symbol names, like _main, _exit,

and _printf, are prefixed with

underscores, as Darwin requires. Most Linux systems don’t require this, so

Linux users should omit the leading underscores from all such names. Unfortunately,

I cannot figure out how to link with ld in Linux, so I recommend trying to

understand what gcc -v your_obj_file.o is doing, and

this might help.

Let me know in the comments if there’s an easy way to use ld when linking your

object files from linux and I’ll be happy to post an edit.

Let’s start with this fragment and get it building, then I’ll cover what it’s doing.

.text

.globl _main

_main:

subq $8, %rsp

movq $0, %rdi

call _exit

Let’s use OSX’s built in assembler (as) and linker (ld).

as nothing.s -o nothing.o

ld -lc -macosx_version_min 10.8.5 nothing.o -o nothing

We should now be able to run ./nothing without any segfaults. Without

-macosx_version_min 10.8.5 I get a warning and my executable segfaults.

Now let’s create a basic generic Makefile to help us automate these steps. Watch your step; archaic syntax ahead.

SOURCES = $(wildcard *.s)

OBJECTS = $(SOURCES:.s=.o)

EXECUTABLES = $(OBJECTS:.o=)

# Generic rule

# $< is the first dependency name

# $@ is the target filename

%.o: %.s

as $< -o $@

default: $(OBJECTS)

for exe in $(EXECUTABLES) ; do \

ld -lc -macosx_version_min 10.8.5 $$exe.o -o $$exe ; \

done

.PHONY: clean

clean:

rm *.o

for exe in $(EXECUTABLES) ; do \

rm $$exe ; \

done

By the time you read this, I’ve already forgotten how half of that code works.

But, this will allow us to run make to assemble and link all of our .s files

individually, and make clean to remove our object and executable files.

Surely you can whip up a better build script? Let me know in the comments

below.

So now let’s go back to our assembly file and go over it line by line. Again, it looks like:

.text

.globl _main

_main:

subq $8, %rsp

movq $0, %rdi

call _exit

.text is the text section. This section defines the instructions that the

processor will execute. There can be other sections as well. We’ll see more

later, but the “data” section

typically has static variables that have been initialized with non null (and non

zero) values, where as “bss” will have static but non initialized values. Also,

there will be a heap and a stack although you don’t declare them as you would

for text or data.

Next up is the global directive. The global directive tells the linker that there will be a section named _main that it may call into, making the _main section visible to other sections. You may be wondering why directives and sections both begin with a dot.

‘.’’ isn’t a valid identifier character in C, so way back when it became common to use ‘.’’ as a prefix in the assembler and linker in order to avoid clashing with C symbol names. This unfortunately was used for both section names and directives, because both can appear in contexts where a simple parser wouldn’t be able to disambiguate otherwise.

I don’t know why they used the same convention for directives and section names, but they did, and it’s not practical to change it now.

Ok now the subtraction instruction. We’ve got a bit to go over with just this one line. The first is the instruction itself. The sub instruction has numerous suffixes that specify how many bytes to operate on. The typical convention for numerous instructions is to have a suffix of b for 1 byte (8 bits), w for a word (2 bytes, 16 bits), l for a long or double word (4 bytes, 32 bits), and q for a quad word (8 bytes, 64 bits). Leaving off the suffix, the assembler will try and guess based off of the operands, which can lead to obscure bugs. So subq operates on 64 bits. Extending this we should be able to recognize that subb operates on 8 bits, subw operates on 16 bits, subl operates on 32 bits, and subq operates on 64 bits. What’s important to understand is that instruction suffix is dictated by the inputs and destination size. See Figure 3-3 of the AMD64 ABI.

Ok now let’s look at the full instruction subq $8, %rsp. The current order of

the operands is known as the AT&T syntax, where the destination is specified

last

(

as opposed to the Intel syntax,

where the destination follows the instruction name ex. subq rsp, 8).

I’m biased towards AT&T-syntax because GCC, LLVM, and icc (at least on Unix-like platforms) all use it, so it’s what I’m used to by necessity. People familiar with assembly languages on other platforms sometimes find it feels backwards from what they’re used to, but it is learnable.

I’m writing my examples in AT&T syntax simply because when I compile my C code from clang with the -S flag, or run my object files through gobjdump, I get AT&T syntax by default (though I’m sure there are flags for either AT&T or Intel syntaxes). Also, the ABI docs are in AT&T. What are your thoughts on the two different syntaxes? Let me know in the comments below.

So when we say subq $8, %rsp, we’re subtracting the immediate value of 8 from

the stack pointer (the register %rsp contains our stack pointer). But

why are we doing this? This is something that is left out from some of the

basic hello world assembly programs I’ve seen. This is the first ABI point I

want to make:

x86-64 ABI point 1: function calls need the stack pointer to be aligned by a multiple of 16 bytes.

By default, they are off by 8 on function entry. See Section 3.2.2 page 16 of the ABI.

Why is the stack pointer misaligned by 8 bytes on function entry? I’m going to punt on the answer to that for a bit, but I promise I’ll come back to it. The most important thing is that that call instruction later on will fail unless we align our stack pointer, which started out misaligned. If we comment it out (pound signs, #, comment out the rest of the line) and make our executable, we’ll get a segfault. You could even add 8 bytes to the stack pointer and our basic example would work (we just need a multiple of 16 remember), but when we learn later (I promise) about how the stack works in x86-64, we’ll see we can mess things up by adding rather than subtracting.

Next up we’re moving the immediate value 0x0 into %rdi. You may have heard that arguments to functions are pushed on the stack in reverse order, but that’s an old x86 convention. With the addition of 8 more general purpose registers, we now pass up to the first 6 arguments in registers (then push the rest, if any, on the stack in reverse order). The convention (in OSX and Linux) is our second ABI point:

x86-64 ABI point 2: The calling conventions for function invocations require passing integer arguments in the following sequence of registers: %rdi, %rsi, %rdx, %rcx, %r8, %r9, then pushing the rest on the stack in reverse order.

See section 3.2.3 under “Passing”. Warning: Microsoft has a different calling convention. This is quite troubling to me, because I assumed that Instruction Set Architectures were created so that the same code could run on two different machines with the same microarchitecture, but because the ISA does not define how arguments would be passed, this ambiguity is left up to the OS implementor to decide. Thus the same code may not run on two different machines with the same microarchitecture if their operating systems are incompatible at the ABI layer.

UPDATE: Further, I just learned that Go, and C code compiled by 6c don’t use the “normal” SysV ABI and calling convention, but have their own.

What our goal is is to call exit(0); where exit is defined in libc, which we

link against during the linking phase with with flag -lc. This is another

punt on system calls. So to invoke exit with the first integer argument of 0,

we first need to move the immediate value of 0x0 into %rdi. Now if you run your

executable from your shell, then echo $?, you should see that the previous

command’s exit code was 0. Try changing the exit code to 42 and verify that it

works successfully.

Ok, well a program that does nothing is more boring than hello world. Now that

we have our build setup out of the way, let’s make a hello world program. If

you’re familiar with ASCII tables, we can use putchar from libc since we’re

already linking to it. Use man putchar to look at its signature and

this ASCII table to move immediate values into a

certain register (remember the

calling convention, point #2) and make sure you setup the stack pointer before

any calls and exit after all other calls.

I’ll leave that up to an exercise for the reader. Let’s use a string and printf.

.data

_hello:

.asciz "hello world\n"

.text

.globl _main

_main:

subq $8, %rsp

movb $0, %al

leaq _hello(%rip), %rdi

call _printf

movq $0, %rdi

call _exit

First up is our data section .data. I previously mentioned the data section

contains global non null and non 0 variables. You can see here that the string

itself becomes part of the binary by using the unix command strings and

passing your executable as the first argument. Further, if you pass your

executable to hexdump you can even see the ASCII codes in hex:

0001020 68 65 6c 6c 6f 20 77 6f 72 6c 64 0a 00 00 00 00

Also, we can run our binary through objdump as well and see the string:

gobjdump -j .data -s hello_world

...

Contents of section .data:

2020 68656c6c 6f20776f 726c640a 00 hello world..

Ok so now we’re moving an immediate value of 0x0 to %al. %al is 1 byte wide, so we use the b suffix on the mov instruction. The next important point of the ABI has to do with functions that use a variable number of arguments (varargs), like printf does:

x86-64 ABI point 3: Variadic functions need to have the number of vector arguments specified in %al.

This will make printf debugging hard without. Also in section 3.2.3 under passing.

If you don’t know what vector arguments are, no worries! I’m not going to cover them. Just know that without this, the contents of %al may work in a basic example, where we haven’t touched %al, %ax, %eax, or %rax yet, but we shouldn’t bank on it being 0x0. In fact we shouldn’t bank on most registers being preserved after a function call. Now’s a good time to talk about volatility:

x86-64 ABI point 4: Most registers are not preserved across function calls.

Only %rbx, %rsp, %rbp, and %r12-%r15 (and some others) are. These are called “call saved” or “non volatile” registers. The rest should be considered “call clobbered” or “volatile.” That means every time we invoke a call like printf, we need to reset %al, since it is the lower 8 bits of %rax which is the 1st return register, so it is always clobbered.

The next instruction loads the effective address of the string relative to the current instruction pointer into %rdi, the first argument for printf. The .asciz directive appends the null byte for us, since C strings are null terminated.

With this knowledge, can you modify hello world to print “hello world 42”, without putting 42 into the string in the data section? Hint: you’ll need a placeholder in your string and need to know the x86-64 calling convention to pass an additional argument to printf.

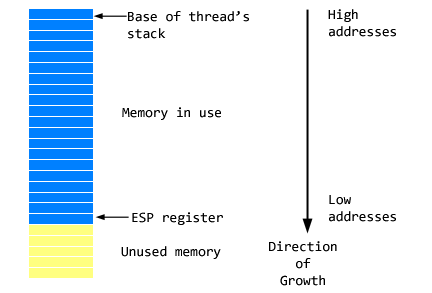

Finally, let’s talk about the stack. When we create automatic variables in C, they are created in the segment called the stack. On x86-64 the stack starts at some arbitrary address (virtual memory backed by physical memory) and “grows” downwards. That is why we subtracted 8 bytes, rather than add 8 bytes to the stack for alignment earlier. The metaphor of a stack of plates is kinda upside-down as additional plates (variables) are going underneath the current bottom plate if you can imagine, in this case. The stack grows towards the heap, and it is possible for them to collide if you don’t ask the OS to expand your data segment (sbrk).

Let’s say we want to call something like memset, which from man memset we can

see takes an address, a value to fill, and a number of bytes to fill. The

equivalent of say this C code:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <inttypes.h>

int main () {

int8_t array [16];

memset(&array, 42, 16);

int8_t* ptr = array;

printf("Current byte: %" PRId8 "\n", *ptr);

++(*ptr);

printf("Current byte: %" PRId8 "\n", *ptr);

++ptr;

printf("Current byte: %" PRId8 "\n", *ptr);

}

Well, that might look like:

.data

_answer:

.asciz "Current byte: %d\n"

.text

.globl _main

_main:

subq $8, %rsp

subq $16, %rsp # allocate 16B

leaq (%rsp), %rdi # first arg, &array

movq $42, %rsi # second arg, 42

movq $16, %rdx, # third arg, 16B

call _memset

leaq _answer(%rip), %rdi

movq $0, %rsi

movb (%rsp), %sil # these two are equavlent to movzql (%rsp), %esi

movb $0, %al

call _printf

incq (%rsp)

leaq _answer(%rip), %rdi

movq $0, %rsi

movb (%rsp), %sil

movb $0, %al

call _printf

leaq _answer(%rip), %rdi

movq $0, %rsi

movb 1(%rsp), %sil

movb $0, %al

call _printf

addq $16, %rsp # clean up stack

movq $0, %rdi

call _exit

This isn’t a perfect example because I’m not allocating space for the ptr on the stack. Instead, I’m using the %rsp register to keep track of the address I’m working with.

What we’re doing is allocating 16B on the stack. Remember we need to keep %rsp aligned on 16B boundaries, making it a multiple of 16B. If we needed a non 16B multiple, we could allocate more than needed on the stack, and then do some arithmetic later when access our automatic variables.

For memset, we need to pass the address of our first argument. In x86-64, the stack grows downwards, but our variables “point” upwards, so %rsp and the higher 16B is the memory addresses of our array, with %rsp currently pointing to the front. The rest you should recognize by now as part of the calling convention.

In the next grouping of instructions, we want to verify that memset set every byte to 42 (0x2A). So what we’ll do is copy the first byte from our array, currently pointed to by %rsp, to the lower 8b of %rsi which is named %sil. It’s important to zero out the 64b contents of %rsi first, since it may have been clobbered by our previous call to memset.

Then we dereference and increment the value pointed to by our array pointer,

++(*ptr) or ++array[0]. Now array[0] is 43, not 42.

In the next grouping of instructions, we print the second byte of our array,

array[1], and get 42 from memset. Now we could try to increment the stack

pointer itself by one, but then the call to printf will fail, so instead when we

load the value of array[1], we do some pointer arithmetic

movb 1(%rsp), %sil.

This is relative addressing, though you’ve already seen this with loading the

strings. You might wonder why I’m not loading the byte in the other

“direction,” say movb -1(%rsp), %sil. Well, that goes back to my point that

while the stack pointer moves down as we allocate automatic variables, their

address and memory they take up “points up.”

Finally, we clean up our automatic variable’s allocated space on the stack. Note that we do not zero out that memory. A preceding function call might overwrite that data on the stack, but until it does or unless we explicitly zero it out, a buffer overrun could accidentally read that data a la Heartbleed.

Now I did promise I would talk about why the stack pointer is misaligned by 8 bytes on function entry. That is because unoptimized functions typically have a function prolog and epilog. Typically, besides creating room on the stack for automatic variables at the beginning of a function, we typically want to save the frame AKA base pointer, %rbp, on the stack. Since %rbp is 64b or 8B and the push instruction will decrement the stack pointer by 8b, this will align the misaligned stack to a 16B multiple. So in function bodies, you’ll typically see:

my_func:

push %rbp

movq %rsp, %rbp

# your code here...

popq %rbp

ret

This great article

explains that you may want to profile your running

application, or look at the call stack in a debugger, and by having a linked

list of stack frames of the function that invoked yours and it’s caller and so

on in a dedicated register makes it trivial to know the call stack at any given

point in runtime. Since we’re always pushing %rbp immediately thereby saving it

on the stack and putting our stack pointer (%rsp) in the base pointer (%rbp)

(later restoring it, %rbp is call saved), we can

keep popping %rbp then moving our stack pointer to that value

to see that quux was called by bar was called by foo

(foo(bar(quux()));). Now you saw that I was able to write code that clearly

worked without the three additonal instructions in the prolog and epilog, and

indeed that’s what happens with optimized code emitted from your compiler.

And since GDB uses something called DWARF (adds symbols to your objects)

anyways, it isn’t a huge issue to remove the prolog and epilog.

So, I think I’ve shown you enough to get started hand writing assembly. To learn more, you should write the higher level C code for what you’re trying to do and then study the emitted assembly by compiling with the -S flag. With clang, you’ll probably see a bunch of stack check guards for each frame, but those just prevent stack buffer overflows. Try compiling simple conditionals (jump forwards), then simple loops (jump backwards) without optimizations. Jumping to sections and calling your own functions should be pretty easy to figure out. Hint: don’t duplicate section names, but the assembler will catch this and warn you pretty explicitly.

Don’t let people discourage from learning assembly because “compilers will always beat you.” “Just use LLVM or libjit or whatever for codegen.” Well, existing solutions aren’t perfect solutions in every scenario. Someday you might be tasked with doing codegen because LLVM is not optimal under certain constraints. You’ll never know if you can beat them unless you try; those most comfortable are those most vulnerable. I’m afraid that if enough people are turned away from learning the lower levels of programming because the higher level is unquestionably better, then assembly will ultimately be forgotten and the computer becomes a black box again. This is something that troubles me and that I see occurring around me frequently; a lot of devs new to web development conflate jquery with JavaScript, and Three.js with WebGL. If you’re around the Bay Area, I’ll be giving a talk at HTML5DevConf on May 22 demystifying Raw WebGL. You should come and check it out.

In summary, remember:

- The stack pointer needs to be aligned by 16B multiples when calling another function.

- Calling convention dictates passing arguments in %rdi, %rsi, %rdx, %rcx, %r8, %r9, then stack.

- %al needs the number of vector arguments for variadic functions.

- Know which registers are call saved (%rbx, %rsp, %rbp, and %r12-%r15 (and some others)) and call clobbered.

Closing thoughts by Dan:

To me, machine code doesn’t feel analogous to this concept of the divine name. I certainly wouldn’t describe it as “like a flawless glass; a light of total understanding streamed through it”. Even if you strip away all the accidental complexity, machine code is still permeated by mundane implementation-oriented concerns. Also, the abstractions which we use to organize and “understand” the program are gone; information is lost.

My imagination of a divine language looks a lot more like an idealized and cleaned-up LISP. It’d be capable of representing all known means of abstraction and combination (in the SICP sense), it might be thought of as a kind of super-language of which all of our real-world languages are just messy subsets.